Medical and psychotherapeutic use

Cannabis has a long history of its use for medical and recreational purposes, which dates back, according to early evidence, to Shen Nung in the 28th century BC. Shen Nung recommended that people use cannabis because of its medicinal properties. The first evidence of marijuana use as a medicine was recently found by archaeologists who discovered traces of marijuana in the remains of a young woman who died, probably at the birth of a child 1600 years ago. The researchers suggested that marijuana was used to speed up the process of birth and to ease the pain associated with it. The information that cannabis was used during childbirth was first found in Egyptian papyrus and Assyrian tablets. Systematic use of cannabis as a therapeutic agent did not take place until the 1800s. For example, a Parisian doctor, Jaco Mauroy, used cannabis in the mid-1800s to treat headaches. Cannabis has become much more widespread thanks to Dr. William O’Shaughnessia, an Irish doctor who was the first in scientific work in 1838 to outline aspects of cannabis use to help with diseases such as rheumatism, pain, rabies, convulsions and cholera.

Cannabis has also been widely used in the United States to treat a variety of diseases. It was appreciated as a therapeutic drug already in the 1900s. At this time, cannabis was mentioned in the collections: United States Pharmacopeia, The National Formulary and in the United States Dispensatory. In the latest collection, for example, cannabis was recommended for the treatment of neuralgia, gout, rheumatism, rabies, cholera, seizures, hysterics, depression, delirium tremens and insanity.

The decline in the use of cannabis in medicine, observed in our century, is the result of two factors. The first is the progress in the development of new drugs and the discovery of new knowledge relating to many diseases and to the methods of their treatment. The second factor is the 1937 Marijuana Fees Act. This legislation has significantly reduced the use of marijuana for medical purposes.

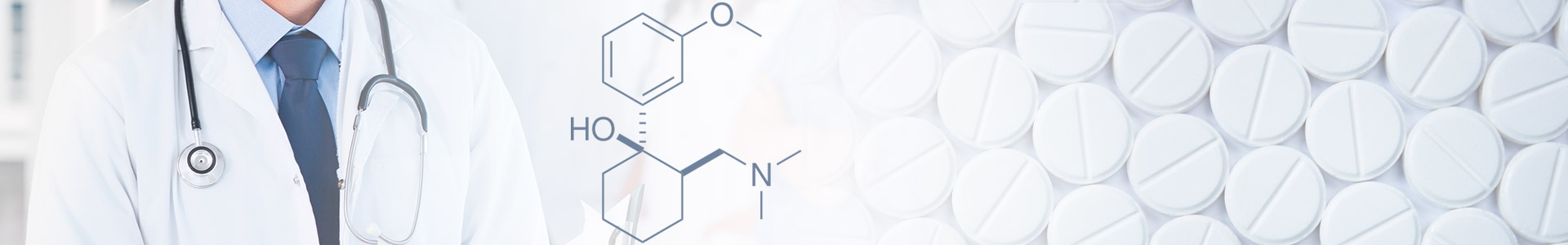

Currently, the use of marijuana for therapeutic purposes is largely limited. This is mainly due to the use of synthetic drugs (such as Levontradol, Nabilone and Marinol), which are chemically similar to cannabis, they are used today for the treatment of certain ailments. These synthetic substances are widely used, since they provide the active elements of the HPS in a more stable form. Synthetic substances also dissolve better. Unfortunately, their disadvantage is the lack of a quick effect on smoking marijuana. When oral administration of synthetic THC before they enter the blood, they first pass through the gastrointestinal system, so absorption slows down dramatically.

Recently, attempts have been made to legalize the use of marijuana for medical purposes. Most of these attempts are stimulated by an increase in the number of marijuana smokers among AIDS patients, who claim that marijuana reduces the feeling of nausea and vomiting caused by the disease, stimulates the appetite, and thus helps them compensate for the weight loss resulting from the disease. One such attempt is the creation of “cannabis clubs” in some major cities of the United States. These organizations buy marijuana in large quantities and supply it (free of charge or for money) to patients with AIDS, cancer, and other diseases. The cannabis club in San Francisco operates quite legally and is under the auspices of city law, which allows medical use of marijuana.

The final resolution regarding the legalization of marijuana for medical purposes will probably not be passed soon. Meanwhile, there are some diseases – especially glaucoma and seasickness – when cannabis is prescribed in a synthetic form, it will be described in the following sections.

“Before making a decision (not to legalize marijuana for medical purposes), we carried out serious research. Marijuana has no recognized medical value.”

Beal Ruzementi, official DEA. USA Today, October 1, 1993

“All that we ask the DEA is to get the hell out of the way of using drugs that have been proven effective.”

John Morgan, Professor of Pharmacology, New York University Medical School, USA Today, October 1, 1993