JOY MESKALINA

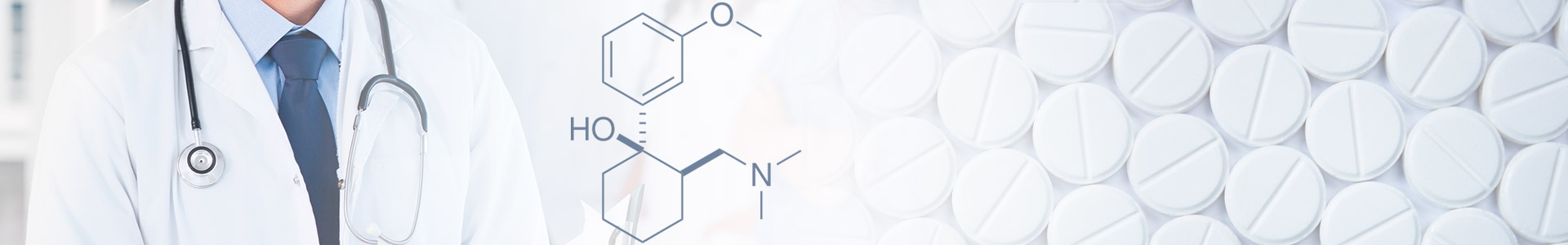

In 1897, Arthur Hefter, Levin’s rival, became the first person to single out and accept pure mescaline. Mescaline is a powerful visionary amphetamine found in the Lophophora williamsii peyote cactus . It has been used for at least several centuries by the Sonora Indians in Mexico. Its use in Peru, where it was extracted not from peyote, but from other types of cactus, has at least several thousand years.

Psychologist and one of the first sexologists Havelock Ellis, following the example of Weir Mitchell, soon presented his description of the pleasures of mescalin.

A vision never resembles familiar objects; they were extremely clear, but nevertheless always new; they were constantly approaching and, nevertheless, constantly elusive resemblance of familiar things. I have seen marvelous, puffy fields of jewels, arranged individually or in clusters, sometimes sparkling and glistening, sometimes cast in a luxurious subdued radiance. Then they exploded in front of my eyes with some similar forms of flowers, and then they seemed to turn into bright butterflies or innumerable folds of wings of some wonderful insects, wings, the transparent fibers of which were iridescent with all the colors of the rainbow … Some monstrous forms appeared , fabulous landscapes, etc. … It seems to us that any scheme that would define in detail the type of vision in accordance with the successive stages of the action of mescalin should be considered as extremely conditional. The only thing that is typical in terms of consistency is that the most elementary visions are followed by visions of a more complex nature.

Mescalin led experimenters to another chemical agent of “artificial paradise”, more powerful than hemp or opium. The descriptions of mescaline states could not but attract the attention of the surrealists and psychologists, who also shared fascination with images hidden in the depths of the newly defined unconscious. Dr. Kurt Beringer, a student of Levin, acquainted with Hermann Hesse and Carl Jung, became the father of psychedelic psychiatry. His phenomenological approach is marked by descriptions of inner visions. He conducted hundreds of experiments with mescalin in humans. The descriptions given by his subjects are simply wonderful.

Then again the dark room. Visions of fantastic architecture again captured me, endless transitions in the style of Moore, moving like waves, interspersed with amazing images of some fancy figures. One way or another, the image of the cross was extremely often present in the inexhaustible variety. The main lines shone with an ornament, sliding to the edges with snakes or dismissing tongues, but always straightforward. Crystals appeared again and again, changing the shape, color and speed of appearance in front of my eyes. Then the images became more stable, and little by little two huge space systems emerged, separated by some kind of feature into the upper and lower half. Shining with their own light, they appeared in infinite space. Inside they appeared new rays of brighter tones and, gradually changing, took the form of elongated prisms. At the same time, they moved. Systems, approaching one another, were attracted and repelled.

In 1927, Beringer published his “magnum opus,” “Mescaline intoxication,” then translated into Spanish, but never into English. This is a very impressive work, it has created a scientific platform for research pharmacology.

The following year, the publication in English of the book by Heinrich Kluwer “Mescal, a divine plant and its psychological effects” appeared. Kluwer, whose work was based on the observations of Weir Mitchell and Havelock Ellis, again introduced the English-speaking world to the concept of pharmacological visions. Especially important is the fact that Kluver took the content of the observed experiences seriously and first tried to give a phenomenological description of the psychedelic experience.

Clouds from left to right across the entire optical field. The tail of the pheasant (in the center of the field) turns into a bright yellow star, the star – into sparks. Moving sparkling screw, hundreds of screws. A sequence of fast-moving objects in pleasant tones. A rotating wheel (about 1 cm in diameter) in the center of the silver patch. Suddenly in the wheel is the image of God, as it is represented in the old Christian images. Intention to see a homogeneous, uniform dark field of view: red and green shoes appear. Most phenomena are much closer to the distance required for reading.