“The device with the medicine is part of me”: I live with pulmonary hypertension

THE HUMAN HEART IS A DIFFICULT ORGAN. His left ventricle pushes oxygen-rich blood into the vessels, through which it is delivered to all tissues and organs. The right ventricle, on the other hand, pushes the blood returning through the veins into the pulmonary artery so that it is enriched with oxygen in the lungs. The pressure in the pulmonary artery differs from the usual one, which was measured more than once at a doctor’s appointment for each person; normally it is 8–20 mm. rt. Art., and if the rates are too high, pulmonary hypertension is diagnosed.

At the same time, it is much more difficult for the heart to work, it begins to increase in size, a person does not feel well, shortness of breath, fainting occurs, it becomes difficult to move. If the disease is not treated, heart failure develops with all possible consequences, including death. Pulmonary hypertension is considered rare and is even included in the list of orphan diseases in Russia – although we are not talking about isolated cases, but, for example, about 500-1000 new diagnoses per year in the United States. Begimai Sataeva told us about life with pulmonary hypertension, about working forty hours a week and about a treatment machine that becomes part of your body.

I am twenty-five years old, I grew up and lived in Bishkek, and in 2015 I left to study gender under the Erasmus Mundus program. Out of six possible countries and universities, it fell to me to study in Poland and the Netherlands, and after graduating from the magistracy in the city of Utrecht, I stayed to live in the Netherlands. Now I work in an international organization, in the department of external relations and share an apartment with two girls, the same young professionals, in The Hague.

Back in Kyrgyzstan, I was worried about a number of symptoms – for some time I ignored them, but when I went to the doctor, I did not receive any specific information. For example, one day (this was in my second year of undergraduate studies) it became difficult for me to breathe. Then I studied and worked, I was late for class, and at some point my heart began to beat violently, my breath stopped and my head began to spin a little. I did not understand what was happening, I stopped, looked around, it became easier for me, I went on more slowly. This began to happen more and more often, gradually becoming my usual rhythm. I connected it with anything: I work a lot, do not sleep at night, jet lag, student life, anemia, and so on. About a year later, I had a short fainting spell, it became difficult to climb stairs, I could no longer walk quickly and, in general, could not withstand physical activity, I quickly got tired.

I was referred to a doctor in the mountain medicine department with suspected heart disease. They made a drip and let me go home. It turned out that the equipment for diagnosing heart pathologies was taken to the regions. In principle, this answer suited me: I had a bunch of other important things to do and projects and did not want to deal with diagnoses and stay in the hospital at all. In general, the process of going to a doctor in Kyrgyzstan is a lot of stress. Queues, a paper system, a million certificates and extracts, a depressing atmosphere. There was no specific diagnosis, and I did not insist – I did not want to be in public hospitals, I simply could not physically run around different offices and floors.

Doctors asked several times if I had taken drugs for weight loss – the disease can also develop because of them

I was diagnosed with pulmonary hypertension in September 2016 when I came to study in the Netherlands. I got on my bike, drove a few meters and fainted. Passers-by crowded around, one of them a doctor who was on a run. I got up, dusted myself off and wanted to go on about my business – I hadn’t even come to my senses after a twelve-hour flight. But an ambulance rushed in, and they simply did not let me go – the doctor gave me an EKG and said that I should go with her to the hospital. They did not immediately understand what was happening there, but they clearly suspected something more serious than fatigue after a long flight. A few days later I fainted again, in the bathroom in the morning. This time, I myself understood that I needed help. I was urgently transferred to the intensive care unit, prescribed several examinations, consultations with a cardiologist and a pulmonologist, and asked my parents to come.

Pulmonary hypertension is of several types and can occur for various reasons, in my case it is idiopathic – that is, it arose on its own, without an obvious reason. The risk can be influenced by genetic factors and, for example, life in the highlands. And the doctors also asked several times if I had taken drugs for weight loss – the disease can also develop because of them. No, I did not take them, but I saw them everywhere and everywhere: in bazaars, in pharmacies, in advertisements on TV and on the Internet. In Bishkek, and throughout the CIS, they are available completely freely. These are teas, tablets, syrups “for body shaping”. I was warned not to take any medication without consulting a doctor.

Pulmonary hypertension begins very slowly, and because of its nonspecific symptoms, it is difficult to diagnose it at an early stage. Shortness of breath, difficulty with exercise, fainting begins. In Central Asia, there is no adequate therapy, people are simply sent home – and the outcomes are the most unfavorable. As far as I know, heart and lung transplants are performed in Russia, but these are extreme measures. In general, it is impossible to completely recover from this disease, but there is supportive therapy that is needed for life. This is exactly what I get.

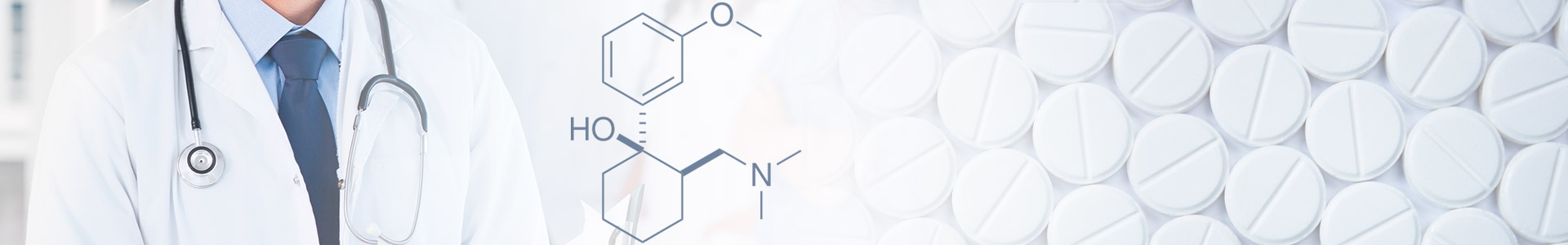

I came to the Netherlands in critical condition, and I was immediately prescribed treatment. I receive the medicine around the clock: a special apparatus is attached to my body in the chest area, which, like a dropper, constantly injects a small amount of the drug. With this device you can live a full life, travel, ride a bicycle, work. I have already ceased to perceive it as something alien – it is a part of me, an additional organ. The therapy is not felt in any way, it does not hurt me, although sometimes wearing the device can cause slight discomfort. At the very beginning, the body got used to it for a couple of months, there was nausea, lack of appetite, fatigue, but then I returned to normal life.

I did not immediately realize and accept my diagnosis – everything happened very quickly. I thought about my studies, my plans, the tooth that I broke when I fell off the bike, and I didn’t think that I would have to carry a device with medicine around the clock. I stayed in the hospital for two months, my mother and sister came to me and they, I think, also did not fully understand what was happening. The doctors and nurses were responsible for everything, I myself did not have to do anything special, so the realization of the diagnosis and new life with the device began to come later, when I was discharged from the hospital. The nurses came to me, taught me how to use and take care of the device, change the cassettes with the medicine, what to do in case of emergency. Gradually, I began to understand what was happening to me and was happening, that I needed to be more attentive in some aspects, more closely monitor my health.

At first it was scary and unusual. After I was discharged from the hospital, they gave me taxi coupons for several months while I got used to getting around the city. I remember looking at girls who were having fun riding their bicycles, and I wondered if I could ever do that. And she was able to, gradually joining the Dutch student life. Now I have almost no restrictions: except that you cannot swim and run marathons, you need to take a shower carefully, change cassettes and treat a vein under sterile conditions, be at home during the delivery of medicines. But I live the ordinary life of an ordinary girl, work forty hours a week, meet friends, travel, sometimes I allow myself a couple of glasses of wine.

However, after graduation, I was going to return home to Kyrgyzstan, and when they told me that I needed to stay in the Netherlands in order to have access to therapy, it came as a shock. I was afraid of the future in the country, I did not understand how to look for housing and work, I did not know the language. But I was lucky with people, I was supported and supported by the family from whom I rented a room in Utrecht. Gerda sometimes jokes that she has two daughters – me and her own daughter Paula. They went with me to all examinations, talked to doctors, explained how things work in Holland, helped in everything. I don’t think I could have done it all alone.

Older relatives constantly insisted that one should not talk

about illnesses to her husband or young man.

In the Netherlands, on the street and in the metro, you can meet people with catheters attached to their faces, oxygen tanks, hearing aids – and no one pays attention to this. At the same time, I remember well the words of my older relatives in Kyrgyzstan – they constantly repeated that all men are unfaithful and that one should not talk about illnesses to one’s husband or young man. It is clear that my therapy is quite noticeable, it is impossible to hide it – and I would not. But at first, when they put the device on me, I was terribly shy of it, I was ashamed of my body, I didn’t tell my friends and family for a long time. I don’t know why I had such a reaction – perhaps because the culture in post-Soviet countries is fixated on female beauty, everyone should have perfect nails, eyelashes, and a figure. This is probably why we still sell and openly advertise the very same drugs for weight loss.

I would like the girls to bother less about their appearance, sincerely love and accept themselves, which is what the experience of life in the Netherlands teaches me – here people, for example, dress so that it is first of all comfortable. At some point, I had an idea for a photo project, but I was not ready to tell my story. It was scary to open up to the public, relatives, friends, acquaintances. But one day an announcement appeared in the tape about the help of a girl with the same diagnosis – I remembered how I suffered myself, and decided that it was time to talk about it.

When I talked with photographers, not all of them understood my idea. We corresponded with Azhara Shabdanova for several months, and it became clear that it was time to shoot, because if you delay, the “spark” and relevance of the project will disappear. I bought tickets to Moscow and we filmed. It was unusual to see myself from the outside. I wear the device every day, but in the photo it looked somehow strange. Then I realized that I just never saw such photos in the media, on billboards or on Instagram. Nobody just talks about this – for Holland it is not something unusual, but for Kyrgyzstan, on the contrary, it is a taboo topic.

When I was preparing for filming, I set several tasks: first, to normalize my own perception of the body, to show that this also happens, and there is nothing special, strange or bad about it. Remove the taboo on the concept of physiology and the body in general. Secondly, I wanted to tell my story from the medical side, to show my therapy, to tell about existing technologies. I would like people to finally start demanding that the health care system should work properly from the state. In the future, I plan to develop a public awareness campaign on pulmonary hypertension, both in terms of body perception and medicine.